Retail Theft Grants Aren’t Fixing Retail Theft. They’re Buying Surveillance.

Across Oregon, and plenty of places beyond, Organized Retail Theft (ORT) grants are paying for equipment that watches everyone while doing little to stop theft where it actually happens: inside stores. The promise was precision. The practice looks like dragnet surveillance with a thin public safety return.

Oregon set up the ORT Grant Program to support costs “associated with addressing and prosecuting organized retail theft,” with the Criminal Justice Commission administering awards. That’s the official frame and the decision-making structure.

Here’s the catch that keeps showing up in budgets: the solicitation and program materials allow spending across personnel and equipment, a wide door for purchases like fixed cameras, mobile trailers, and automatic license plate readers (ALPR) that plug into regional databases. In other words, the rules let agencies build surveillance infrastructure and still count it toward “retail theft” goals.

What about locally?

Read our report on the Springfield ORT Grant Spending.

Take Springfield’s own reporting window from August 2024 to March 2025. The Springfield Police Department logged $330,528 in ORT spending across three quarters, with $185,628 (56%) for equipment and $134,640 for personnel. Reported outcomes: 17 arrests, 100 items recovered, $3,411 in recovery value, and zero citations or DA referrals. That’s roughly $19,443 per arrest and a penny of recovered value per dollar spent. The least expensive quarter performed best; after the equipment surge, outcomes didn’t improve.

That one example doesn’t stand alone. It lives inside a broader funding landscape where “equipment” keeps rising to the top of the shopping list, even when results are vague, delayed, or not really about retail theft at all. The state task force that champions ORT funding has touted agency highlights and large awards, but it also openly points to ALPR purchases as an ORC-funded tactic, including a documented example in Eagle Point. When vehicle surveillance becomes the headline purchase under a retail theft grant, the strategy is tilting away from the retail floor and toward general-purpose policing.

How we got here

If you’ve read vendor brochures, you’ve seen the narrative: create “virtual perimeters,” watch for plates, and push alerts to law enforcement. A seamless fix for organized theft, they say. Flock Safety’s marketing leans hard on that frame, tying its ALPR products to organized retail crime outcomes. The pitch is smooth, confident, and aimed at public budgets.

But most theft isn’t a cinematic heist crew in getaway cars. It’s a mix: a few coordinated fencing operations and a lot of walk-in/walk-out cases tied to addiction, poverty, or opportunism. For those incidents, plates don’t help much. Prosecutable cases depend on clean in-store evidence, quick intervention, cooperative retailers, and prosecutors who get usable packages. Plate hits after someone leaves the lot don’t fix chain-of-custody or witness issues. They don’t turn a fuzzy camera angle into an ID. And they certainly don’t turn low-level theft into a strong DA referral by themselves.

Part of this is policy design. The program allows equipment, period. That flexibility makes sense if the gear demonstrably supports ORT outcomes, but without strict reporting standards, “equipment” becomes a catchall for surveillance systems with broad policing value and minimal retail-theft specificity. The ORT page and solicitation emphasize the program’s purpose, but they leave room for hardware buys that function like general surveillance. That’s policy drift baked into the rules.

Then there’s the pressure cooker of public messaging. Industry groups publicize eye-popping “shrink” numbers, losses in the tens of billions. These blur the line between shrink (which includes error, fraud, and breakage) and organized retail theft. Those headlines show up in hearings and city memos, and they often become a fast pass for big technology buys. But shrink is not proof that a license-plate dragnet will reduce theft in your neighborhood. It’s a talking point, not an outcome tied to a specific tool. Even worse, the industry retracted the very numbers that are being used to drive ORT programs.

Oregon’s not alone

What’s happening here reflects a national trend: public safety grants using flexible “equipment” categories to fund surveillance infrastructure first and measure impact later, if at all (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). ALPR networks expand because they offer broad law enforcement utility (stolen cars, warrants, regional data-sharing), but those same traits make them a poor fit for the specific job of reducing in-store theft and building strong cases. Vendor marketing floods the zone with anecdotes; meanwhile, local reports like Springfield’s show heavy equipment purchases with no clear uptick in retail-theft outcomes.

You can see the contradictions in official narratives too. The same Oregon task force materials that highlight ALPR purchases also showcase sweeping arrest counts linked to “retail theft operations,” which often mix general enforcement with theft missions. That’s not necessarily bad policing, but it muddies the question the public is asking: does this spending reduce organized retail theft as advertised? Without standardized, local reporting tied to clearly defined ORT measures such as arrests, referrals, recovered value, and case dispositions, there’s no way to tell.

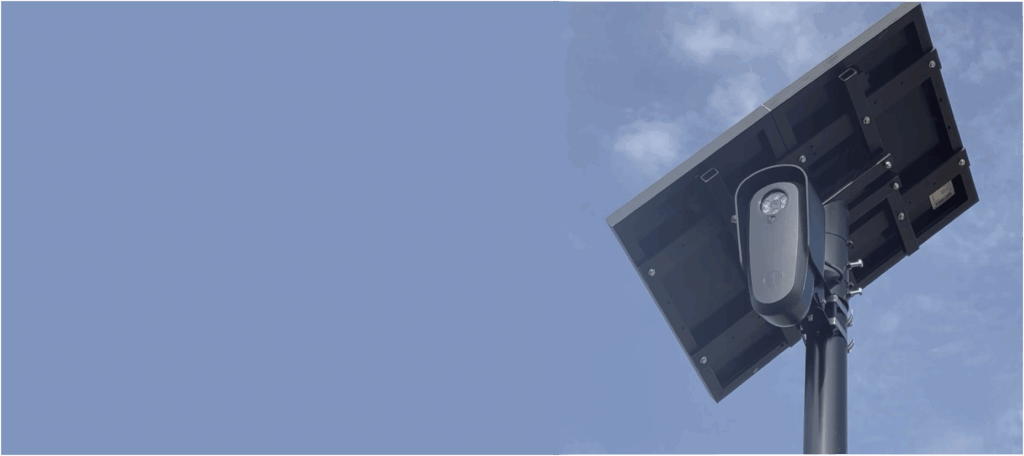

Surveillance isn’t neutral. When a city installs plate readers on main drags and shopping corridors, the data doesn’t just capture suspects: it captures everyone. Residents driving to work; teens leaving practice; families running errands. And because these systems generate alerts with varying accuracy and pass data through regional networks, they can also produce stops and searches that fall hardest on people who already bear the brunt of over-policing. The harm isn’t abstract. It’s the knot in your stomach when another pole-mounted box shows up by your local grocery store, and no one can tell you what it’s catching besides all of us.

Meanwhile, small retailers keep asking for practical help: more predictable, coordinated operations; training that results in clean evidence; and pathways that don’t criminalize poverty while still holding repeat offenders accountable. Those aren’t algorithm problems. They’re human problems, best solved by people, not plates.

A better way to spend the ORT dollar

If these grants are going to continue, cities can pivot to strategies that match the problem and respect the public:

- Fund targeted, time-bound operations with retailers who can testify and provide same-day evidence packages prosecutors can use.

- Require quarterly reports that separate “organized retail theft” outcomes from general policing stats, with itemized equipment tables (devices, vendors, activation dates, hosting fees) and a clear go-live timeline tied to results. The current state framework can support that level of specificity if cities ask for it.

- Put community outcomes first: worker safety improvements, store design that reduces harm without turning aisles into lockboxes, and targeted services for repeat low-level offenders tied to substance use or survival.

- Press pause on expanding ALPR and mobile surveillance trailers with ORT dollars until there’s independent local proof that they reduce organized retail theft, not just recover stolen cars or flag warrants. That’s the program’s stated goal; hold the spending to it.

A brief return to Springfield, because it matters

It’s worth noting that Springfield publicly celebrated a two-year ORT award of more than $500,000 and promised stronger retail-theft outcomes. Residents deserve to see those results, clearly and consistently, in the city’s own reporting. When the local numbers show heavy equipment purchases and stagnant outcomes, the response shouldn’t be to throw more gear at the wall. It should be to tighten the connection between dollars spent and cases made, and to explain what’s working, what isn’t, and what changes next quarter.

Because this isn’t just about theft. It’s about trust. When public money is routed through a program that allows broad equipment purchases, the burden shifts to agencies to prove that the tools they buy actually serve the stated aim: addressing and prosecuting organized retail theft. They should do this without expanding surveillance far beyond the problem at hand. On both counts, the current pattern isn’t persuasive.

The bottom line

Oregon’s ORT grants were meant to fight organized retail theft. Too often, they’re underwriting surveillance systems that cast a wide net and deliver thin results on the problem they’re supposed to solve. The state’s rules allow the drift. Vendor marketing encourages it. Local ledgers, Springfield’s included, show how the invoices outpace the value.

Communities can insist on something better: measured operations that produce real cases, safer stores that protect workers and customers, and spending that stays tied to the narrow mission voters were promised. If a tool truly helps, it’ll show up in the next quarterly report, and in fewer thefts that store managers and neighbors can actually feel. Everything else is noise, and an ever-growing wall of cameras keeping tabs on people who are just trying to buy groceries.

Bold move? Maybe. Necessary? Absolutely.